One Family, Two Children and a 16-Year Quest for Answers

11.23.2021 | Amanda Maier

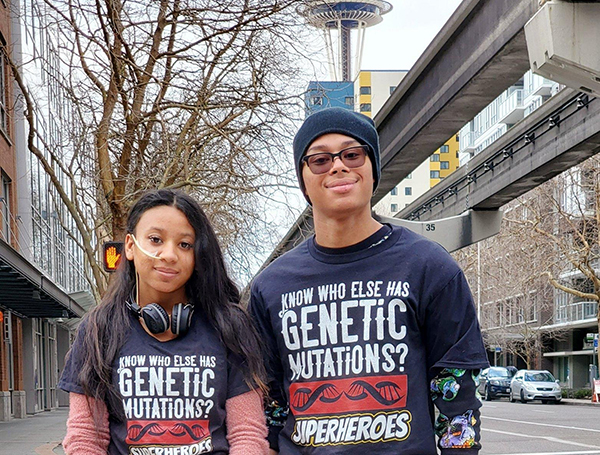

Sabrina and Reiff Castillote knew something was wrong with their daughter Maleea’s health when she was just 5 days old. Then, their 6-year-old son Malachi’s behavior became concerning.

For over 15 years, Sabrina and Reiff took their children to countless specialists, but they never received a clear diagnosis. “We were told our daughter was considered ‘failure to thrive,’ without any real answers to as to why,” Sabrina said. “Some providers thought Malachi might have autism and ataxia, but not all their symptoms lined up.”

Finally, in 2019, they got an answer.

A rare genetic disorder

In 2017, Malachi was riding his bike to high school when he was struck by a car. Malachi was taken to the local hospital to treat his concussion and get a brain scan; he was also experiencing an increase in tremors that spread across his whole body.

The incident ultimately led the family to Dr. Dararat Mingbunjerdsuk at Seattle Children’s. During their meeting with Dr. Mingbunjerdsuk, Sabrina and Reiff shared their concerns about Malachi’s health. After several follow-up appointments, Malachi underwent a genetic test that yielded uncertain results.

Malachi was referred to the Biochemical Genetics team, who confirmed a diagnosis through enzyme analysis and targeted genetic testing for Sabrina and Reiff. On Sept. 26, 2019, the family learned Malachi had a rare terminal genetic disease called neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis 2 — or CLN2, a form of a group of inherited disorders known as Batten disease.

The team recommended Sabrina and Reiff’s other two children, Maleea and Azriel, also undergo genetic testing. Just three days before Maleea’s 14th birthday, the family learned she too had CLN2. Azriel, Sabrina and Reiff’s younger son, tested negative.

The news that two of their children had CLN2 was devastating. “I think there’s something uniquely difficult about receiving a diagnosis like this when your children are older,” said Sabrina. “When a child is younger, parents can take on a lot of the burden, but our kids were almost 14 and 18 when they were diagnosed. They were in school and had lives and dreams of their own. Malachi was the school mascot for four years and loved powerlifting and playing the piano, and Maleea was a cheerleader and figuring out how to be a young lady. Those things were ripped away and ‘normal’ life stopped. Our lives changed forever.”

Starting treatment

There is no cure for CLN2, so it is crucial patients begin receiving treatment as quickly as possible to slow the spread of symptoms. Unfortunately, because CLN2 is such a rare diagnosis, few healthcare organizations offer treatment. At the time, Seattle Children’s did not, so Dr. Irene Chang, the family’s genetic provider at Seattle Children’s, put them in touch with Children’s Hospital of Orange County— the closest facility that treats CLN2.

On Oct. 21, 2019, the family flew to California for appointments at CHOC. Malachi and Maleea each needed brain surgery to place a reservoir port underneath their scalp. The port would lead into the middle of their brains and allow them to receive biweekly enzyme medication via brain infusions; this would help slow the symptoms of CLN2 but would not cure the disease. Because of the nature of Malachi and Maleea’s condition, the family began wearing masks before the pandemic started.

Sabrina, Reiff, Maleea and Malachi stayed near CHOC for several months before eventually returning home on Dec. 29, 2019. Over the coming months, the family would fly or drive from their home near Seattle to California every other week for Malachi and Maleea’s brain infusions.

Brain infusions closer to home

While the Castillote family was in California, they stayed in touch with Irene about the possibility of receiving their brain infusion treatment at Seattle Children’s, which would allow the family to stay together during treatment, and for Malachi and Maleea to remain in school more.

In February 2020, a team from Seattle Children’s — Dr. Chang, Leah Kroon, Kelsey Pearson and Susan Holtzclaw — visited CHOC to receive training about Malachi and Maleea’s specialty brain ports. Then, Pearson created a process to begin offering the treatment at Seattle Children’s.

“We weren’t starting completely from scratch; we had experience treating some other patients via brain infusions, but CLN2 was a new disease for Seattle Children’s and required we use a new medication,” Pearson said. “Our Infusion Advanced Practice Provider team worked with Neurosurgery, Biochemical Genetics, Pharmacy and the brain tumor teams to create new processes for the medication and access to the port. We also needed to train care teams on the infusion procedure, the medication itself and how to manage potential patient reactions.”

In March 2020, Maleea and Malachi received their first infusions at Seattle Children’s.

Brain infusions are an intense and invasive method to receive medication treatment; every infusion requires the patient’s head be shaved. Until a care team can identify the right combinations of medication, patients can experience incredible sickness, fatigue and pain due to the infusions. After Malachi’s third infusion, he had to be hospitalized for three days with vision problems, a side effect of the infusions.

In 2020, the family asked Seattle Children’s about receiving treatment via chest ports, rather than brain ports, a method that is easier and less invasive for patients but does require a unique and complex surgery. Dr. Jason Hauptman, who helped establish Maleea and Malachi’s brain infusion treatment at Seattle Children’s, connected with a neurosurgeon at another institution to learn about the innovative surgery he’d need to perform to transition to a chest port.

In December 2020, Maleea and Malachi underwent the surgery. Today, they are among the first people in the world to receive this treatment using the chest port configuration.

What comes next

Sabrina and Reiff are grateful Malachi and Maleea can receive infusion treatments closer to home, and to Seattle Children’s care team for paying attention to little details that make their care more manageable — like ensuring the family has adjacent rooms so they can go back and forth to visit their children during the seven-hour treatment sessions.

Going forward, Maleea and Malachi will continue receiving biweekly infusions in Seattle and visit CHOC every six months for care management and continued diagnostic tests.

Ultimately, the Castillotes hope their relationships at Seattle Children’s and CHOC, and outreach via social media and CLN2 conferences, can help make things a little easier for future patients. “Like other families with rare diseases, when we received the diagnosis, we had to piece a lot of things together — where to go for care, the latest research, mental health support and resources. My goal is to help have information like that ready for future families up front,” said Sabrina. “We’ve lucked out with two good teams — CHOC for research and care management, and Seattle Children’s for infusions. We’re in the race against time until there’s a cure.”