COVID False Positives Found in Lab Workers

Online publication date: Oct. 13, 2022

Online publication date: Oct. 13, 2022

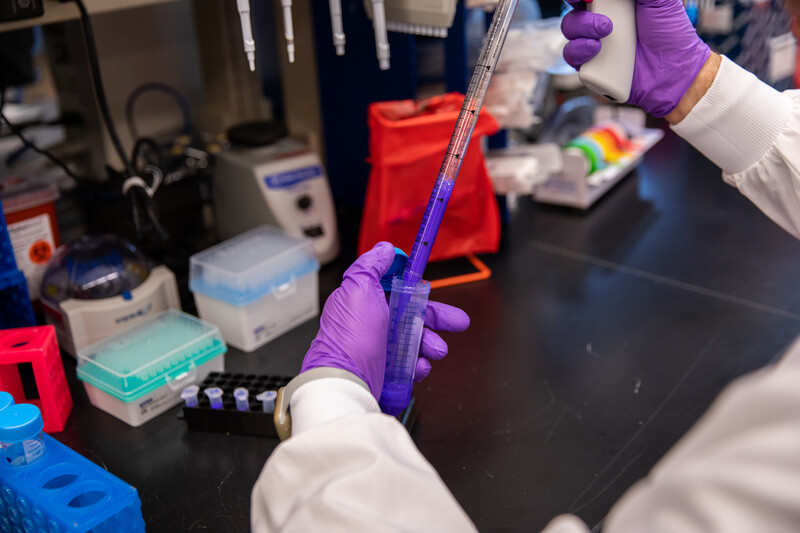

For a very small number of people, a positive COVID test may more accurately reflect where they work than the presence of a viral infection. Seattle Children’s Research Institute scientists reported in Microbiology Spectrum on a group of asymptomatic workers from one laboratory who all tested positive for COVID-19. Further investigation found these were false positive tests for the virus because their positive results came not from the virus’ RNA, as expected, but came instead from a usually harmless bit of DNA called a plasmid, commonly used in labs to study the proteins produced by viruses.

“Plasmids infect bacteria, and we use them all the time in the lab to make proteins,” said virologist and study leader Dr. Lisa Frenkel, who co-directs the Center for Global Infectious Disease Research and is a professor in the departments of Pediatrics and Laboratory Medicine at the University of Washington School of Medicine. “And here, plasmid DNA got in the noses of people who worked with it and seemed to persist.” The study also showed that the plasmid can be spread to other members of a person’s household.

Frenkel said the number of asymptomatic people who test positive and work with SARS-CoV-2 plasmids in labs is unknown. “Most are unlikely to be in studies that test them weekly even when asymptomatic,” she said.

More importantly, the new study revealed that plasmids can linger in the nose — probably within bacteria — for weeks and interfere with clinical diagnostics tests. When physicians interpret diagnostic results, Frenkel said they should consider a patient’s occupational exposure as well as their medical history.

Frenkel, whose work usually focuses on HIV, did not originally set out to study lab workers or plasmids. But in March 2020, as COVID case counts grew worldwide, her lab and multiple colleagues at Seattle Children’s pivoted to work on SARS-CoV-2, and they began looking for biomarkers that could predict how a person would respond to infection. They launched a clinical trial that monitored a group of people on a weekly basis by PCR to detect individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 test who became infected but didn’t show symptoms.

As they analyzed the data, the researchers realized that four of the asymptomatic subjects in their study all worked together in the same lab.

“We knew the principal investigator of that lab, and we knew what they were working on,” Frenkel said. Researchers in that lab had been working with a plasmid with DNA that encoded a protein produced during SARS-CoV-2 infection.

That connection raised a question: Could the diagnostic tests be picking up the plasmid, rather than the virus? After all, PCR tests detect genetic material from the virus. To find out, the researchers analyzed nucleic acids taken from the nasal swabs of the four co-workers and one additional participant, a partner of one of the lab workers who was also asymptomatic but testing positive.

In all cases tested, the material came from the plasmid, not the virus itself. “Ingrid Beck, a senior scientist, proved that it was DNA, not RNA, and that they had it in their noses for weeks,” either in nasal tissues or in bacteria, Frenkel said. The researchers were most likely exposed to the plasmid through their lab work.

“While plasmids are generally safe, our detection of plasmid DNA in the nasal secretions of laboratory workers for weeks after they had stopped working with the plasmid shows the potential for these reagents to interfere with clinical tests,” Frenkel said. “It emphasizes that occupational exposures in the preceding months should be considered when interpreting diagnostic clinical tests.”

Contributing authors from the research institute include Dr. Noah Sather, also an affiliate associate professor in the Department of Global Health, University of Washington School of Medicine; Dr. John Aitchison, co-director of the Center for Global Infectious Disease Research and a professor in the Department of Pediatrics, University of Washington School of Medicine; Dr. Whitney Harrington, also an assistant professor of pediatrics, University of Washington School of Medicine.

Frenkel Lab contributors include first author Ingrid Beck, Sheila Styrchak, Daisy Ko, Alyssa Oldroyd and Samantha Hardy, as well as the Harrington Lab’s John Houck and Yonghou Jiang. Leslie Miller, Dr. Fred Mast and Song Li from the Aitchison Lab contributed, as did the Sather Lab’s Vladimir Vigdorovich, Nicholas Dambrauskas, Andrew Raappana and William Selman.

The study was supported by Seattle Children’s Research Institute, the Clinical and Retrovirology Research Core and the Molecular Profiling and Computational Biology Core of the University of Washington/Fred Hutch Center for AIDS Research, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

— Colleen Steelquist