Meet Javi

I Say Yes to H.O.P.E.

By Javi Barria

I learned to downhill ski in January 2020, seven years after I was first admitted to Seattle Children’s Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine Unit (PBMU). It seemed fitting to be in the mountains – a place that still terrifies me, but also where I’ve made some of my best memories.

Being able to see the beauty in the great outdoors shows me how far I’ve come since that January day in 2013 when generalized anxiety disorder put the brakes on my 15-year-old brain and left me unable to walk, eat or read.

My journey through crisis

My mental health started deteriorating in middle school. I kept telling myself I was just having a rough couple of weeks while I hid under tables, hit my head and lashed out at anyone who tried to help. Weeks turned into months of nonstop anxiety until I experienced what would be the first of many full-blown panic attacks.

My mental health started deteriorating in middle school. I kept telling myself I was just having a rough couple of weeks while I hid under tables, hit my head and lashed out at anyone who tried to help. Weeks turned into months of nonstop anxiety until I experienced what would be the first of many full-blown panic attacks.

Less than a year later, during my freshman year of high school, I was admitted to the PBMU for three months. That’s where I started my journey of H.O.P.E., which stands for Hold On, Pain Ends.

Seattle Children’s PBMU is an acute care facility. That means the team does absolutely everything to de-escalate kids in crisis so they can go on to long-term care with a therapist or in a residential facility.

My team got me through my darkest days by getting to know me as an individual and believing in me, even when I didn’t believe in myself. Their constant support, therapeutic care and love without platitudes – combined with daily heart-to-heart talks – helped me stabilize so I could move to a behavioral treatment center in Tacoma, Wash., where I lived for a year and a half.

Even after my discharge from the residential center in Tacoma, I needed a few more shorter stays on the PBMU. Each time, I got stronger and I found something new to fight for.

Creating change – for myself and others

Today, I’m more able to deal with change and more confident in myself and in my coping skills. I sometimes feel guilty for having moved beyond my most crippling issues, and I worry that I’ll lose opportunities if people find out about my mental health history.

Today, I’m more able to deal with change and more confident in myself and in my coping skills. I sometimes feel guilty for having moved beyond my most crippling issues, and I worry that I’ll lose opportunities if people find out about my mental health history.

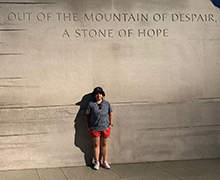

Then I remember what they taught me on the PBMU: It’s okay to not be okay. It’s a mantra that helped me travel to Washington D.C. on behalf of children’s hospitals in 2019. There, I told my story to federal legislators and advocated for early intervention programs and state-mandated response services for kids in crisis. If we can get to them sooner, they won’t have to go through so much pain.

I want to keep telling my story to blow all the stigmas about mental health out of the water. For kids who are struggling in silence (or denial), I want them to know there’s no shame in therapy and they are not alone. For kids in crisis, I want to be an example that it gets better. You have to find a reason to live.

I still fight every day, but I keep going because I am worth it.