Pulmonary Atresia

What is pulmonary atresia?

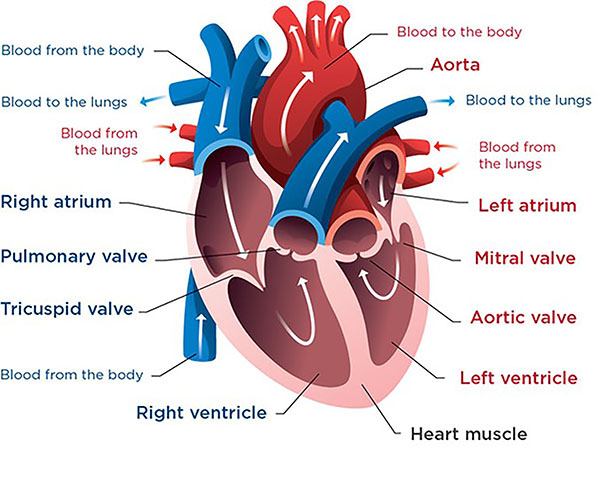

This is a normal heart. In pulmonary atresia, the pulmonary valve is missing or blocked.

This is a normal heart. In pulmonary atresia, the pulmonary valve is missing or blocked.Pulmonary atresia (pronounced PULL-mun-airy ah-TREE-sha) is a very rare, complex birth defect of the pulmonary valve. “Pulmonary” refers to the lungs, and “atresia” means missing or blocked. The pulmonary valve acts like a door that allows blood to flow from the right ventricle of the heart through the pulmonary artery to the lungs to pick up oxygen.

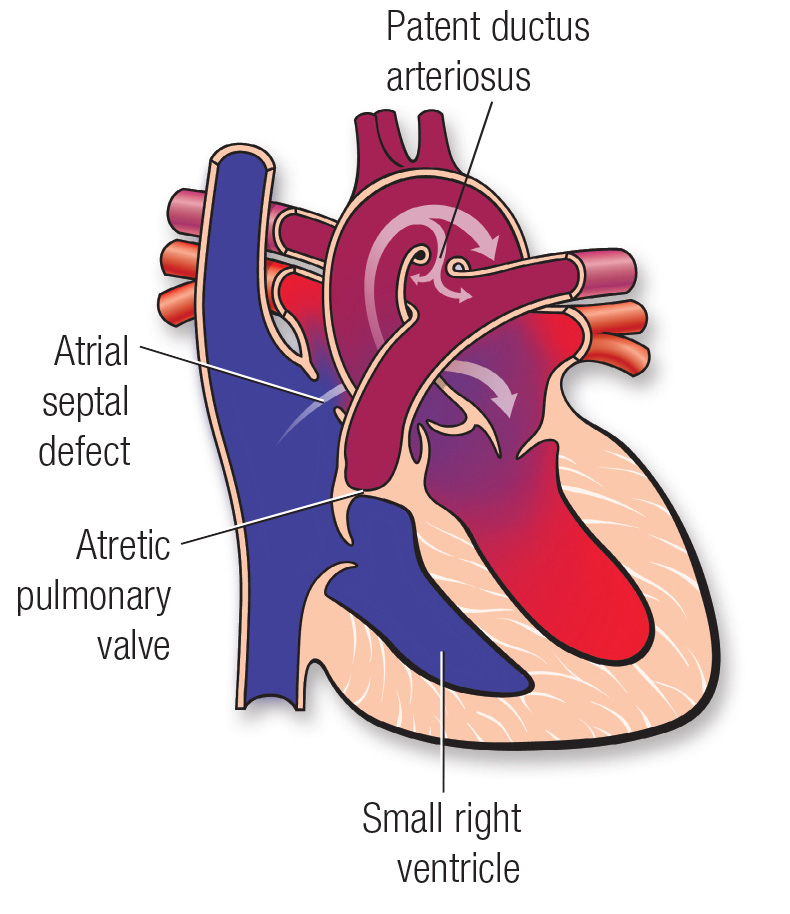

In babies with pulmonary atresia, the pulmonary valve is missing or blocked. This means there is no way for blood to get from the right ventricle to the pulmonary artery. The main pulmonary artery or its branches may be small or not formed correctly. Sometimes they do not connect to each other at all.

Babies with pulmonary atresia get blood to their lungs by different paths since the normal path is blocked. Even so, they do not get the normal amount of oxygen to their bodies, which causes cyanosis.

From heart.org. ©2009, American Heart Association, Inc.

From heart.org. ©2009, American Heart Association, Inc.Other factors that may affect your child’s health include:

- The size of the valve that allows blood into the right ventricle (tricuspid valve)

- Whether there’s a hole in the wall between the ventricles (ventricular septal defect, or VSD)

- Whether the right ventricle is normal sized, small or not fully developed and how well it works

- The size of the branches of the pulmonary artery and how they connect

- If there’s a problem with another organ, such as your child’s brain or kidneys

- If your child has a chromosomal or genetic issue

- If your baby is born early (preterm) and how much they weigh at birth

-

What paths can blood take in babies with pulmonary atresia?

Newborns have a blood vessel between their aorta and pulmonary artery. This blood vessel, called the ductus arteriosus, normally closes shortly after birth. In babies with pulmonary atresia, it may be the only way blood gets to their lungs. Doctors can keep the ductus arteriosus open with medicine to allow enough blood to travel to the lungs.

Some babies with pulmonary atresia have a hole in the wall between their ventricles (VSD). In these babies, blue (oxygen-poor) blood comes from the body into the right atrium. Next, it flows into the right ventricle. Then it goes through the VSD into the left ventricle, which pumps it through the aorta to the rest of the body. Blood gets to the lung arteries from the ductus arteriosus or similar blood vessels from the aorta.

If your baby does not have a VSD, the blood coming into the right atrium goes to the left atrium through an opening in the wall between the atria. This opening, called the foramen ovale, is normal in newborns and tends to close after birth. Next, blood goes from the left atrium to the left ventricle and then into the aorta. Some of the blood that enters the aorta goes through the ductus arteriosus into the pulmonary artery and to the lungs.

“I contacted Seattle Children’s [for a second opinion], and it was there that I learned a lot more about my baby’s diagnosis. They made me feel more at ease.” — Sarah Ouellette, whose son Greyson received care for pulmonary atresia at Seattle Children’s after being diagnosed prenatally at another facility.

What are the symptoms of pulmonary atresia?

Most babies with pulmonary atresia show symptoms during the first few hours after birth. They may be diagnosed after having a pulse oximetry screening in their birth hospital when they are about a day old. In some babies, it may take a few days for symptoms to appear.

If your baby has pulmonary atresia symptoms, they may have these:

- Skin may look blue or purple tinged, mottled (different shades or colors), grayish or paler than usual; the lips, mouth, gums, fingernails or toenails may look bluish (cyanosis)

- Fast breathing

- Working hard to breathe

- Tiring easily while feeding

Heart Center at Seattle Children's

How is pulmonary atresia diagnosed?

-

Fetal diagnosis of pulmonary atresia

Doctors can diagnose pulmonary atresia when a baby is in the womb using a fetal echocardiogram (fetal echo). This is a special ultrasound that uses sound waves to view and make pictures of a developing baby’s heart during pregnancy. The results are interpreted by a pediatric heart doctor (cardiologist) who specializes in fetal congenital heart disease.

Your obstetrician may refer you for a fetal echo if your family has a history of congenital heart disease or if a routine prenatal ultrasound shows a problem.

Seattle Children’s Fetal Care and Treatment Center team can care for you when you are pregnant if your developing baby has a known or suspected problem.

-

Diagnosing pulmonary atresia after birth

To diagnose this condition, your child’s doctor will examine your baby and use a stethoscope to listen to their heart. In children with this condition, doctors often notice cyanosis, and sometimes they hear a heart murmur — the sound of blood moving in the heart in a way that’s not normal.

The doctor will ask for details about any symptoms your child has, their health history and your family health history.

Your child will need an echocardiogram test so the doctor can see how their heart works.

Your child will probably need other tests as well. These include:

- Chest X-rays

- Cardiac catheterization

- CT (computed tomography) scan

- ECG or EKG (electrocardiogram)

- MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) of the heart

How is pulmonary atresia treated?

Your child’s doctor will suggest some procedures and treatments right away to improve your baby’s blood flow. Other procedures may be done when your baby gets older, such as open-heart surgery to repair or replace the valve. Most babies can be helped with surgery.

We provide comprehensive care for children with pulmonary atresia.

Medicine

Your doctor may give your baby medicine (prostaglandin) to keep the ductus arteriosus from closing. This gives blood a way to get to your baby’s lung arteries when the normal path between the heart and lungs is closed. If your baby is diagnosed before birth, the delivery team will plan to start this medicine soon after birth.

Catheterization

Your baby may need cardiac catheterization to enlarge the opening between their atria (foramen ovale). Doctors use a balloon to stretch open the narrow pulmonary valve (balloon valvuloplasty). This process may also be used to place a mesh-like tube, called a stent, in the ductus arteriosus to keep it open and let blood flow from the aorta into the lung arteries.

If your baby has several complex lung artery pathways, your baby’s heart doctor may recommend a cardiac catheterization, CT (computed tomography) scan or MRI (magnetic resonance imaging). These methods can help doctors clearly see where the pathways are and plan the next steps, such as surgery.

Surgery

Your baby will need 1 or more surgeries to improve their blood flow.

The exact procedures and timing depend on your child’s condition, including how serious it is and whether they have other heart defects. The surgeries may be done in stages during your child’s first few years of life.

First, your child’s doctor may suggest surgery to place a shunt between the aorta and the pulmonary artery to increase blood flow to the lungs. If your baby has a pulmonary valve but it’s blocked, the doctor may suggest surgery to open or replace it.

Later, your child may need one of these types of surgery:

- Bidirectional Glenn procedure: If your child’s right ventricle is small but big enough to do some pumping, your child may have surgery to direct some oxygen-poor blood from their body to their pulmonary artery without going through their heart first. This surgery is called the bidirectional Glenn procedure. This reduces the workload for their right ventricle.

- Fontan procedure: If your child’s right ventricle is too small to do any pumping, your child may have surgery to direct all oxygen-poor blood from their body to their pulmonary artery without going through the heart first. This surgery is called the Fontan procedure. It is done after the Glenn procedure. If your child has a Fontan procedure, they get coordinated, ongoing, team-based care afterward through our Fontan Clinic.

- Other surgeries: Your child may need other surgeries based on their condition, such as surgery to close a ventricular septal defect.

Our doctors are very experienced with the procedures needed to treat pulmonary atresia, with outcomes that are among the best in the nation. See our statistics and outcomes for surgeries related to single ventricle defects.

Transplant

Sometimes babies with pulmonary atresia will need a heart transplant. The heart transplant team at Seattle Children’s performs many transplants each year for children with this or other heart problems that cannot be controlled using other treatments. Read more about our Heart Transplant Program and our exceptional outcomes.

Pulmonary Atresia at Seattle Children’s

-

The experts you need are here

- Children with pulmonary atresia receive compassionate, comprehensive care through Seattle Children’s Heart Center. The Heart Center team includes more than 40 pediatric cardiologists who diagnose and treat every kind of heart problem. We have treated many babies with pulmonary atresia.

- Our doctors and surgeons are experts in the treatments your child may need. These may include surgery, cardiac catheterization or, in some cases, a heart transplant.

- Often our catheterization specialists can place a stent to keep the ductus arteriosus open. This allows more blood to get to the lungs until they are older and able to have heart surgery to improve their blood flow.

- Our pediatric cardiac surgeons perform more than 500 heart procedures yearly, including heart transplants for problems that cannot be controlled using other treatments. Our surgical outcomes are among the best in the nation year after year.

- We also have a pediatric cardiac anesthesia team and a Cardiac Intensive Care Unit ready to care for children who have heart surgery. General anesthesia is a medicine we give to people before surgery so they are fully asleep during the procedure.

- Our Single Ventricle Program brings together specialists in cardiology, nutrition, social work, feeding therapy and neurodevelopment to support your child’s health between surgeries.

- Your child’s team includes experts from other areas of Seattle Children’s based on their needs, like neonatologists, pulmonologists, geneticists, speech and language pathologists and many others.

-

Care from birth through young adulthood

- If your developing baby is diagnosed with pulmonary atresia before birth, our Seattle Children’s Fetal Care and Treatment Center team works closely with you and your family to plan and prepare for any care your baby may need.

- Your child’s treatment plan is custom-made. We use a team approach to plan and carry out their treatment based on the specific details of their heart defect. We closely check your child’s needs to make sure they get the care that is right for them at every age.

- We have a special Adult Congenital Heart Disease Program to meet your child’s long-term healthcare needs. This program, shared with the University of Washington, transitions your child to adult care when they are ready.

-

Support for your whole family

- We are committed to your child’s overall health and well-being and to helping your child live a full and active life.

- Whatever types of care your child needs, we will help your family through this experience. We will discuss your child’s condition and treatment options in ways you understand and involve you in every decision.

- Our Child Life specialists know how to help children understand their illnesses and treatments in ways that make sense for their age.

- Seattle Children’s has many resources, from financial to spiritual, to support your child and your family and make your experience as smooth as possible.

- Many children and families travel to Seattle Children’s for heart surgery or other care. We help you coordinate travel and housing so you can stay focused on your child.

- Read more about the supportive care we offer.

Contact Us

Contact the Heart Center at 206-987-2515 for an appointment, second opinion or more information.

Providers, see how to refer a patient.

Related Links

- See a picture (American Heart Association).

- Cardiac Catheterization Procedures

- Heart Center

- Heart Surgery

- Heart Transplant Program

- Single Ventricle Program

Paying for Care

Learn about paying for care at Seattle Children’s, including insurance coverage, billing and financial assistance.