Masking and Visitation Changes: Due to high rates of respiratory illnesses in our community, we’ve made changes to our masking and visitation guidelines. Learn more.

Focusing on solutions to reduce health disparities leads to better health outcomes for all. That’s a point made clear by Seattle Children’s efforts to reduce central line-associated bloodstream infections, also known as CLABSI.

A central line is a tube that is put into a patient’s blood vessel to administer fluids, medications, or address other medical needs. There are many risk factors that increase the likelihood of an infection in a central line, including inserting lines for patients with immune compromising conditions or who require intravenous nutrition, as well as frequent handling of the device.

Dr. Danielle Zerr is the medical director of Infection Prevention at Seattle Children’s. As a pediatric infectious diseases doctor, she has partnered with several departments, including the Center for Diversity and Health Equity and the Center for Quality and Patient Safety, to investigate and reduce CLABSI in inpatient units across the system. She, along with Seattle Children’s Program Manager of Patient Safety Shanda Johnson and Clinical Nurse Specialist Megan Stimpson, lead this work.

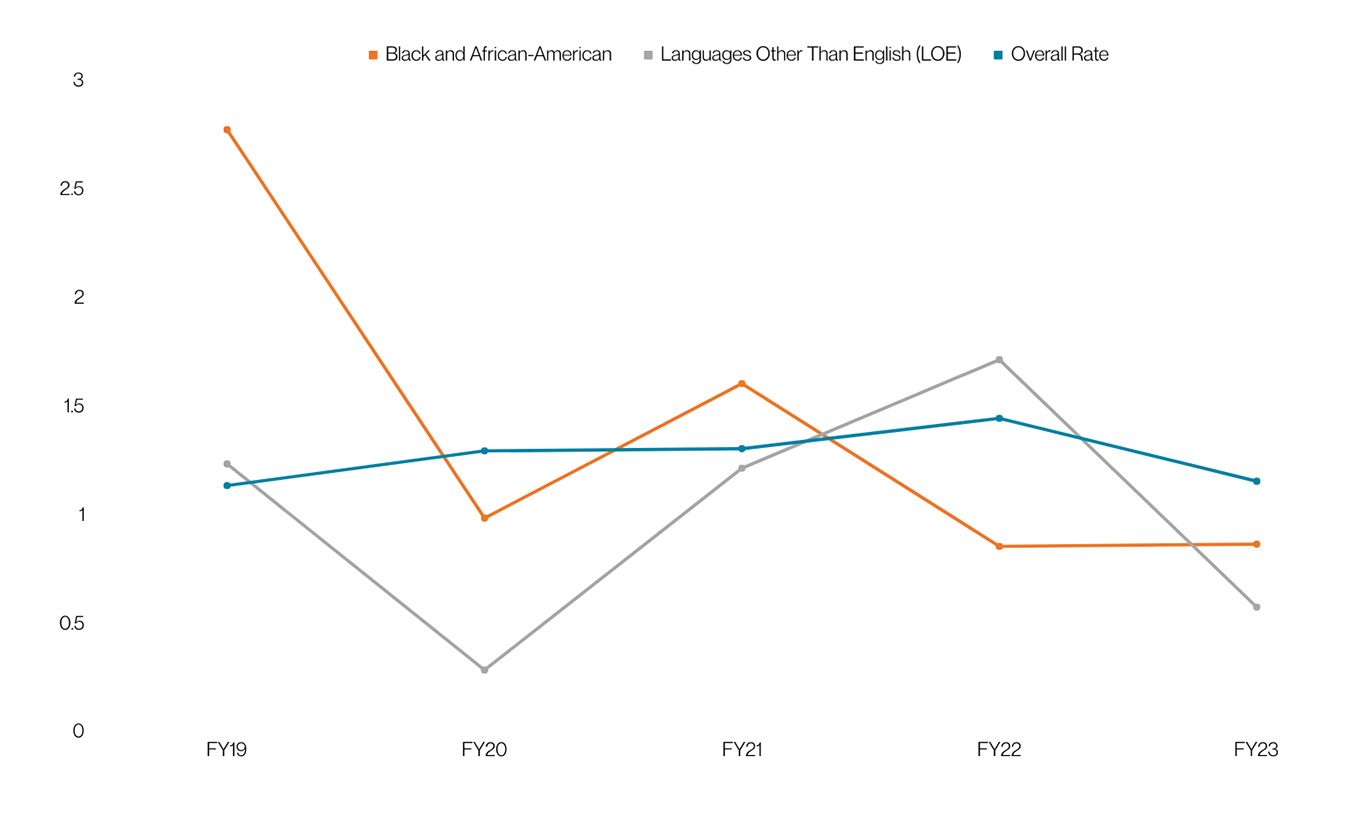

When reductions in CLABSI plateaued in late 2019, Zerr and the team began focusing on specific patient groups, asking the question: “Are there differences in CLABSI rates between patient groups?” Looking at data stratified by patient race, ethnicity and language, they found that Black and African American patients as well as patients who use a language other than English showed higher rates of these infections.

“There isn’t a biological reason for [these disparities],” Zerr shared. “Performing this analysis was a very important step. It allowed the team to identify that we had a problem, share the information with others, and get help figuring it out.”

Data specific to patient identity provided an opportunity for Seattle Children’s to investigate these preventable disparities, prompting additional research into existing practices. For example, “CLABSI Champions” was an existing care team role tasked with observing the care and maintenance of a central line; however, the team found that in some units this observation was being done less frequently with Black and African American patients and patients who use a language other than English in some units.

Kelli (right) and her son Issac’s (left) experience caring for a central line during Isaac’s cancer treatments helped inform an improved central line education program for all patients.

Kelli (right) and her son Issac’s (left) experience caring for a central line during Isaac’s cancer treatments helped inform an improved central line education program for all patients.This learning provided a chance for correction. A multidisciplinary group of Seattle Children’s staff, families, and care providers was established to further explore the disparities and design improved interventions to bring down CLABSI rates.

Former family advisor Kelli Williams’ experience with CLABSI is two-fold: She is both a Seattle Children’s workforce member, and she has a son who had a central line placed for his cancer treatments. Given her unique experience with central lines and Seattle Children’s, Williams was involved in the early efforts to investigate and address this disparity.

“When we received our [central] line care training, this was a new diagnosis for our son. We didn’t know the ins and outs of the hospital or working with providers, and we had a lot of questions — questions we were afraid to ask or didn’t know how or who to ask,” Williams explains. Over time, Williams and her family realized the importance of asking questions, but she acknowledges that many families encounter barriers in patient advocacy.

“I challenged the [CLABSI team] to think about and be mindful of the feelings and emotions [of families] that come to us with a cancer diagnosis. All of sudden we’re kind of like nurses with all these things to do at home, and we’re not trained in the medical field.” Williams experienced her own difficulties in learning to prevent CLABSI, but she can’t imagine how challenging it would be for families who use a language other than English.

To learn about the central line experience first-hand from families, the CLABSI team partnered with the Patient and Family Experience team to facilitate interviews with parents of children with central lines. Families who identified as Black or African American as well as families who use a language other than English shared perspectives and observations about working with care teams on central lines, zeroing in on the challenges they faced and ideas for improvement.

Using this valuable information gained from families, a series of interventions were launched to improve the central line experience and reduce CLABSI.

New central line care videos are now available to help families visualize the steps to safely caring for their child’s central line at home.

New central line care videos are now available to help families visualize the steps to safely caring for their child’s central line at home.A primary concern from families was centered around central line education materials. “Being prepared to take care of your line in the hospital and knowing what to expect when you go home with a line was terrifying for a lot of people,” Stimpson shared. One patient described filming the care for a central line on their cell phone to remember what to do when they went home. Now, patient materials on central lines are translated into five languages and counting. The team also created videos in English and Spanish that families can reference when a central line is placed for their loved one as well as a simple roadmap graphic to explain the care steps.

As for the observation of care of the central line across units, the CLABSI team first made the disparity known to all units and then brought on a new role to ensure that every patient was receiving the same great care. The “central line nurse” is a new specialized position whose entire job is centered around central line placement, observation and safety.

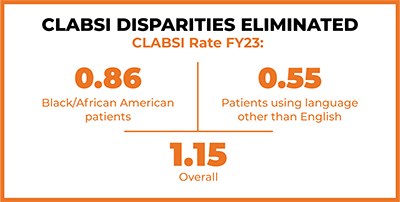

These efforts have eliminated CLABSI disparities for Black and African American patients and patients who use a language other than English.

For healthcare professionals, the results are encouraging. “Before, it was a little overwhelming to think about why this was happening and what can be done to make it better. But our work shows that a systematic approach involving a multidisciplinary team that includes family representatives can make a difference,” Zerr shared.

Now that detailed metrics are available by race, ethnicity and language, care teams can monitor CLABSI rates more effectively and hold themselves accountable to providing the best care to all patients.

“The first steps we took were being transparent with the data, publicizing the data and putting together a multidisciplinary group to develop interventions. Very quickly, the rate fell,” Zerr said. Since the work to reduce CLABSI disparities started in 2019, the overall rate of inpatient CLABSI dropped to 1.15 infections per 1,000 line days in fiscal year 2023. For Black and African American patients, the rate as of September 20, 2023, was 0.86 infections per 1,000 line days, and 0.55 for patients who use a language other than English. Not only did the focus on differences in CLABSI rates reduce the inpatient CLABSI disparity, but it eliminated it altogether.

“The first steps we took were being transparent with the data, publicizing the data and putting together a multidisciplinary group to develop interventions. Very quickly, the rate fell,” Zerr said. Since the work to reduce CLABSI disparities started in 2019, the overall rate of inpatient CLABSI dropped to 1.15 infections per 1,000 line days in fiscal year 2023. For Black and African American patients, the rate as of September 20, 2023, was 0.86 infections per 1,000 line days, and 0.55 for patients who use a language other than English. Not only did the focus on differences in CLABSI rates reduce the inpatient CLABSI disparity, but it eliminated it altogether.

Another important takeaway: the reduction in disparities did not only impact marginalized populations. Once the focus on inequities was established, the CLABSI infection rate for hospitalized patients dropped across all groups. “It’s a reason why everyone should engage in this work,” Zerr emphasized.

The success in reducing CLABSI disparities at Seattle Children’s has been widely shared among the medical community. Earlier this year, JAMA Pediatrics published a study that explored the racial, ethnic and language disparities in CLABSI rates. Stimpson co-authored this publication, alongside other medical and public health professionals at Seattle Childrens, including Zerr. The study points to the importance of assessing hospital quality metrics for disparities to create targeted interventions to improve care for everyone.

Other lessons learned from Seattle Children’s experience have been featured in additional studies. A 2022 publication emphasized what medical providers learned during the hospital equity work: that creating transparent data can expose disparities, inform ways of addressing them, and lead to entirely new solutions and innovations in care.

These findings have been a focus among the Solutions for Patient Safety (SPS) collaborative, a group of more than 140 pediatric hospitals focused on improving safety culture, decreasing common patient and employee harms, and eliminating disparities.

“We are leaders in the safety disparities work,” Johnson shared while explaining that the SP2’s mantra of “All Teach, All Learn,” has encouraged network hospitals to learn from Seattle Children’s efforts.

Not only will the work to monitor and address CLABSI disparities among Black, African American, and those using languages other than English continue, but the team is now also evaluating CLABSI by new variables including sexual orientation and gender identity, other racial and ethnic groups, and by type of health insurance (i.e. commercial insurance, Medicaid/Medicare, etc.).

Improving central line equity is something that is now embedded in the way the CLABSI team addresses infection rates — it’s built into their lexicon. “It’s now normal for us to talk about [reducing disparities] in the same context of reducing CLABSI overall.”

“At the end of the day, we’re making Seattle Children’s a safe place — an equitable place — and providing quality care,” Johnson said. “It brings me joy that we’re part of this work.”

Cover photo: Kelli Williams, Former Family Advisor with Seattle Children’s and current Philanthropy Advisor Program Manager with Seattle Children’s Foundation